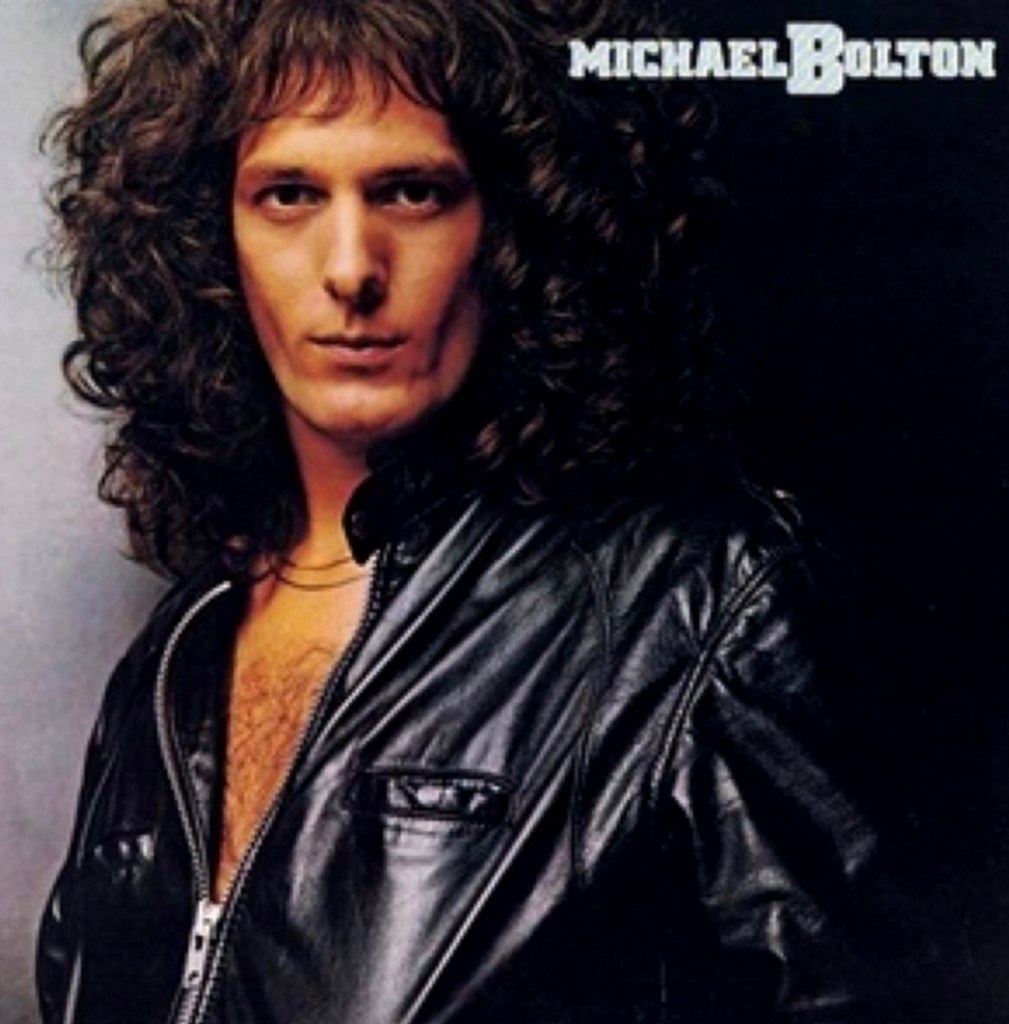

It starts with the “Fools Game” album by Michael Bolton released in 1983, back when Bolton was trying to be Sammy Hagar instead of the soul Bolton we came to know.

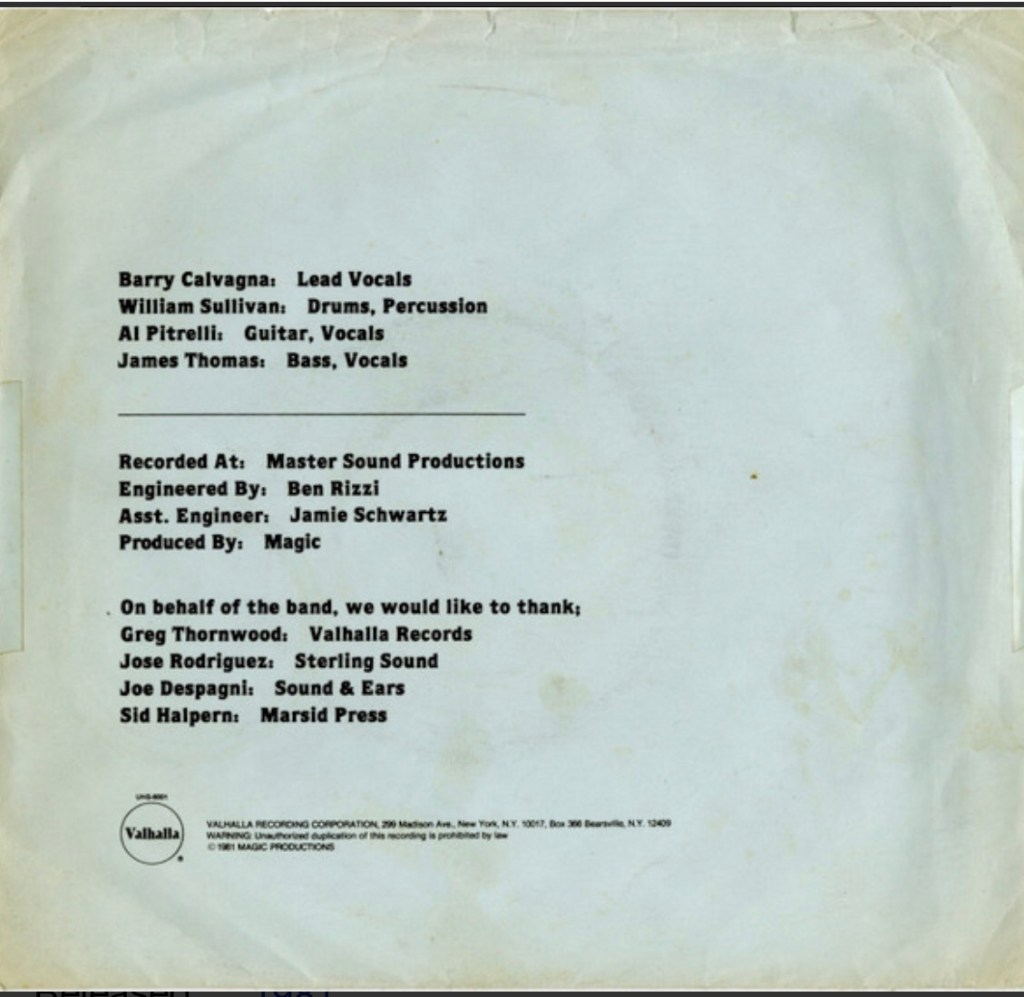

Actually it goes back a few years to 1981 and a band called Magic and a 7 inch single called “Too Much Too Quickly” that had Al Pitrelli playing guitar.

So before Bolton and Berklee there was MAGIC.

They used to rehearse in the basement of a video arcade in East Meadow.

Back to Bolton.

Bruce Kulick and his brother Bob, play guitar on the studio album. Aldo Nova goes a guest solo. Even Bolton shreds a little bit, who started off as a guitarist first, singer second. While the album is a great slab of melodic rock, it didn’t really do anything commercially.

But it gave Bolton enough momentum for the label to fund a follow up in “Everybody’s Crazy” (released in 1985) with Bruce Kulick doing all the lead guitars this time around in the studio. However Bolton was still trying to imitate David Lee Roth, which was a stupid move, as there is only one DLR and Bolton wasn’t it. The album was a financial loss and it did not chart.

However, the label didn’t want to lose too much money on the album, so they put Bolton on the road. However this meant a new backing band was needed as Bruce Kulick accepted the Kiss gig, something which he held until 1996. As a side note, Kulick did got his mate Bolton to co-write a song with the band called “Forever” which was released in 1989 on “Hot In The Shade”.

The new backing band for Bolton would have keyboardist Mark Mangold, who was also the co-writer on the “Fools Game” and “Everybody’s Crazy” albums with Bolton. He also co-wrote “I Found Someone” with Bolton for Cher.

The rest came like this.

Al Pitrelli read the credits on the “Everybody’s Crazy” album and noticed that the people who played on the album had other gigs. He called up his friends, Tony Rey, Chuck Bonafante and another bassist. They learnt a bunch of Bolton tunes, tracked down Bolton’s manager and then offered themselves as his touring band. However the bassist spot went to Bruno Ravel who was called in by Bonafante as Bolton took a disliking to the original bassist brought in by Pitrelli.

For Ravel, it was a dream gig for the 21 year old that lasted six months. On a side note, he had a failed bass gig for an act called “White Lion” because he didn’t like how Bratta and Tramp wouldn’t allow anyone else to write with them.

And if all the names in Bolton’s touring band sound familiar they should, as bands like Danger Danger and Saraya come to mind. Tony Rey would go on to write and produce songs for a lot of mainstream artists.

Pitrelli and Bonfante would also get together regularly in different projects like “Place Called Rage” with Tommy Farese on vocals, “Morning Wood” with Tony Harnell on vocals and “Flesh And Blood” which also included Mark Mangold.

Al Pitrelli by this time had dropped out of Berklee College Of Music. During his time there he became friends with keyboardist Derek Sherinian and drummer Will Calhoun who would go on and join Living Colour.

After he left, he was studying jazz with John Scofield. This is a by-product of growing up in a household that liked Sinatra. Pitrelli’s first Kiss album was thrown out by his dad.

But you can’t keep a rock head down. One thing about rock music is that it is a lifestyle. From Kiss, Pitrelli started to digest Rush, Yes, Led Zeppelin, Aerosmith, Allman Brothers, Mahogany Rush and Hendrix. Then came Eddie Van Halen, an accomplished riff meister and revolutionary shredder.

But Pitrelli’s two biggest influences are Gary Moore and Jeff Beck. Both of these players can move a room full of people with just one note. And that one note is more powerful than a hundred notes. But if they wanted to shred, press the pedal to the metal, they could do that as well. The key word here is balance. Balance between chops and feel.

Suddenly, Pitrelli was seen as a rising star. The Bolton tour (although regional) was his first big break which gave him contacts within the industry. But as the tour progressed, ticket sales stalled and after six months the tour was wrapped up and the touring band sent home.

Ravel was less than impressed with Bolton’s antics and treatment of them, and Pitrelli saw him as mean. In Bolton’s defence, he was pushing 30 and felt that this was his last chance of making it as a solo artist, so he took it out on the people trying to help him make it.

On a sidenote, Bolton also recorded a tape full of demos with just his voice and an acoustic guitar. These demos started to do the rounds with the label execs who wondered why Bolton was singing rock music when his voice was better suited for soul and R&B.

For all of the members, the Bolton tour was a learning experiencing about survival in the music business. Pitrelli knew that survival and making a living in music, depended on playing with anybody and everybody.

Ravel wanted to have his own band but he knew that in order to get to that stage he needed to play with others to make a living.

Enter Talas.

This band was founded by bassist Billy Sheehan in 1971. They went through drummers like Spinal Tap did.

By 1986, Talas lost their founder to David Lee Roth but Talas still had a deal with A&M Records to do one more record. Sheehan gave the band his blessing to go on and meet this commitment.

Vocalist Phil Naro enlisted Jimmy Degrasso on drums, Al Pitrelli on guitar, Bruno Ravel on bass and Gary Bivona on keyboards.

But that final album never got out of the demo stages and Talas was dead when Sheehan did an about face on allowing the band to use the name after word got around that Ravel wore a “Billy Who?” t-shirt that a fan had gave him.

And since the band couldn’t use the name, A&M pulled their deal as well.

While the guys couldn’t use the Talas name, the embryo of what would become Danger Danger was there.

Pitrelli meanwhile jammed and played on the “Funk Me Tender” album from Randy Coven released in 1986. He also did a small club regional tour with Coven.

And then Jimmy DeGrasso left to join Y&T replacing Leonard Haze.

In 1987, a song originally penned by Pitrelli and Ravel called “Temptation” made its way to Phil Kennemore (via Jimmy DeGrasso) and it became track three on the Y&T album “Contagious” which was the bands Geffen debut. If you haven’t heard it, press play on it. It’s a great melodic rock cut.

The first proper incarnation of Danger Danger would have Al Pitrelli on guitars, Steve West on drums, Bruno Ravel on bass and Kaesy Smith on keyboards. Phil Naro was the first vocalist and he was quickly replaced by Mike Pont and then Pont was replaced that same year by Ted Poley. The demo this version of the band recorded got the band its recording contract with Epic Records.

But by 1988, Pitrelli left Danger Danger or he got the boot, depending on who you believe due to having disagreements with the labels A&R rep.

As Pitrelli described it, he was in the band for about 18 months, played a lot of nickel and dime gigs and when the band made a left turn in musical direction, he went the other way. And by the end of it, Danger Danger taught him lessons on what to never do again.

Pitrelli was replaced by Tony Rey who would also leave to join “Saraya” with Andy Timmons taking the guitar slot from 1989 to 1993. You can hear Pitrelli’s playing in Danger Danger on the album “Rare Cuts” released in 2003.

After this Pitrelli re-formed an earlier band he had called “Hotshot” with Pont on vocals and after a very promising six song demo called “The Bomb” failed to get them a label deal he disbanded “Hotshot”.

Pitrelli then got call from an old friend, another Long Island kid called Steve Vai.

Yep that Steve Vai.

He told Pitrelli to audition for David Lee Roth’s band as Vai had just left to join Whitesnake. Vai actually said that he “wanted Pitrelli to take his place in Roth’s band”. Vai even took time out to teach Pitrelli all the guitar parts. Pitrelli nailed the gig and Roth was thrilled.

But whatever went down afterwards was never spoken of again. Roth to this day has never mentioned the Pitrelli audition of the Roth band at all.

In between, Pitrelli was jamming and writing songs with Joe Lynn Turner. Turner had a deal with Elektra who he would rename as Neglektra.

The label kept Turner in development hell between 1988 and 1991, only to drop him and keep the songs he wrote during this period. Because in label land, it’s embarrassing if an artist you dropped makes it with another label on the backs of the songs they had with the previous label. The same thing happened to Dee Snider during this period who was also with Elektra.

In order to get by, Pitrelli did some session work and one of those sessions got a full release. It was a funk soul album by “Philip Michael Thomas” called “Somebody” which did nothing commercially. Thomas is known more as an actor who dabbled in music.

Pitrelli was at the crossroads. He didn’t know what to do anymore. He was in and out of bands, filling in spots perfectly but really struggling to get his own project off the ground. The lack of a reliable income weighed heavily on him. Trying to make it in the music industry was proving tougher than he thought. He had all the chops and players of lesser abilities graced the covers of the magazines. To make some extra cash he was teaching guitarists. He was also married and a conversation with his father-in-law was about him going into carpentry.

But that jam session with Roth impressed drummer Gregg Bissonette a lot and a few months down the track Bissonette recommended Pitrelli to Alice Cooper.

In 1989, Pitrelli got an offer he couldn’t refuse; to become Alice Cooper’s musical director and guitarist in the touring band supporting the album “Trash”.

Musical director meant to rethink the older songs to sound more contemporary so they wouldn’t sound out of place next to the current songs from the “Trash” album. He also got his Berklee roommate Derek Sherinian his first major gig.

On another side note, the students that Pitrelli had would move on to another guitarist called John Petrucci. Yep that same Petrucci from Dream Theater.

As the 80s drew to a close, Al Pitrelli survived in the music business without actually being involved in a full length release. Because one of the lessons he learnt touring was that the real money was made on the road.